Up A Creek, Without A Paddle

During my trip around Mongolia, I had my Lonely Planet, and ridiculously, everyone else in the truck, including our guide, did too. So, like a load of pilgrims with our holy books always at hand, we bounced through the countryside, faithfully checking facts and figures as we went. I've had guide books on most of my journeys, and they have often overwhelmed me; here is this book detailing every "point of interest," custom, accommodation, "off the beaten path" destination, food, and merchandise available for purchase, in the land, and suddenly the wide open possibility of travel is narrowed, and the planet is no longer lonely, because someone is in your head telling you what is interesting and what you will be missing if you take too much time to reflect on what you've just seen.

sheep and herder

sheep and herderA sense of busyness was to be avoided at all costs. So, I figured that through a combination of internet access and other travelers I would get any information that I needed, and I left the books on a shelf next to a couch in the common area of a Singapore hostel on my way out the door at 5:45 am.

India, from the second I stepped off the plane, has been more of a shock than I ever imagined anything could be. I had heard about the staring, but there it was, in the flesh, making me want to disappear, forced by the pressure to keep my head down and eyes averted, making it even harder to find my way around. I had heard about the cows, but there they were, in reality, serenely munching on trash, drinking from puddles, and pissing and shitting in the street as people and cars jostled and honked around them. There I was, in reality, in Delhi, a city of over 15 million souls, without a map, without a friend, and without any idea how to get out of there.

as common as a cockroach

as common as a cockroachThat's how I got syphoned into the elaborate system of connections and graft that is the tourism industry in India. I was told by "Mickey," the agent at the "tourist information" office, that these offices had been set up a few years ago after an Australian woman was raped and killed outside the Delhi International airport.

This, according to him, had been the last in a series of incidents that prompted the government to set up a better system for tourists. At the moment, that sounded plausible, but now after the string of lies and exaggerations included in his pitch that have been uncovered along the road, I'm not even really sure that was a government office. He pushed Rajasthan, where I am now, hard, as the place to see and buy all things traditionally Indian; it is, for him, the place you must see if you are to say you have seen India. It is an incredible place, but I'm sure his appreciation of it has to do more with the greater possibility of graft due to extended contacts in the area.

the rat temple of Bikaner

the rat temple of BikanerFor 1,200 USD I have a car and driver for 17 days, 26 nights accommodation, and 3 train tickets. As I realize how much things really cost here, I wonder exactly where all that money is going. I got it out of my driver that he is paid 2000 Rupees a month from the company. This breaks down to 66 R a day, or $1.45, and my accommodations are usually listed between $9 and $20 per night.

There are also hidden expenses, like everyone who would like to be tipped. When I asked my driver, shocked by his salary, how he can possibly live on 66 Rupees a day, he said that he depends on tips and commissions. He explained that there are two kinds of shops he can take me to, commission (only for tourists), and government. If he takes me to commission shop he will get 100 Rupees, whether or not I buy anything. If I do purchase something he gets 5%. At government shops the prices are fixed at a fair value (he tells me) and there is no bargaining. From those he takes a 2% commission on my purchases. If he actually told me this, there must be more layers that he didn't expose. In any case, his prospects for this trip are low; I haven't been in a single shop so far, and shortly after he gave me this information he proceeded to first offer, and then beg to bestow, his sexual services. That's a story for another chapter, but the incident has completely doused my generousity.

After hours in the tourist office experiencing what I guess were mild symptoms of typhoid, I agreed to a 17 day circuit of Rajasthan, a land of fortresses, deserts, camels, and castles, 1 night in Agra, home of the Taj Mahal, 2 nights in Khujoraho, home of the famous Kama Sutra temples, and then 8 nights in Varanasi, a holy spot on the river Ganges. After that, I travel by train to Mumbai, and then again by train to Goa. At Goa, I will have used my last train ticket and will be, once again, sans plan.

backside of a temple

backside of a temple

Money has not been my main problem with the package I bought; the problem is predictability. I wanted to travel without any pressure of moving on and without any limitations on what could happen or where I might end up. This trip was intended to be a practice of reacting to things as they present themselves, rather than attempting to exert control over the future, so I spent the first few days of my trip feeling pissed off with myself (on top of everything else I was pissed off about) for caving in to Mickey's tactics. What I should have done was buy one train ticket out of Delhi and make onward plans as I went. I was so preoccupied with the subversion of my goals for the trip that I'm sure I missed a lot. But, something finally penetrated my mood.

On our second night, and second stop, in Bikaner, I checked into a tolerably comfortable room. At dinner, in the courtyard, I was told by the greasy waiter, who stood there and talked to me for the duration of my meal, that there was a Heritage Hotel very nearby. Heritage Hotels are fantastic places: fairytale forts and palaces that have been meticulously preserved, restored and retrofitted with all the modern conveniences. I've been checking them out along the way, and they're affordable. I've decided that if I have a honeymoon, me and my king will travel by the "palace on wheels" train, resplendent in polished teak and brass, and sleep like royalty every night in Heritage Hotels.

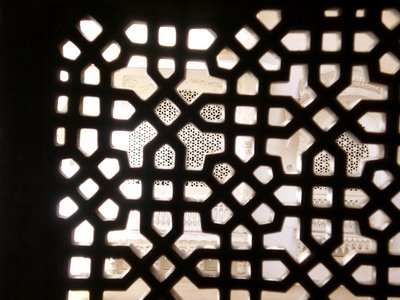

carven screens through carven screen

carven screens through carven screenMy waiter insisted on accompanying me to the nearby palace, but I managed to escape him. I entered the marble corridors and looked around: portraits of Maharajas and Maharanis, a pool in the atrium, a deep-cushioned bar with ancient weapons on the wall. Somehow, I was interested only in a clinical, detached sort of way. Finally, I went to the center of the enormous, darkened central courtyard and sat on a marble bench surrounded by palms. I stopped my notation of objects and their connections to my own store of information and I listened to the night birds singing, and saw the palace spires silhouetted against the stars. Then the feeling enveloped me: I have never seen, I have never understood, I have never even really imagined, anything like this before.

I have read Rudyard Kipling and plenty of other British colonial literature, and I'm sure I've seen many images of this kind of place; I must have internalized so many pictures and stories that I believed these magnificent structures were familiar, but I was suddenly, fortunately, bursting with wonder at the opulence, the delicacy that has endured for ages, the collective genius, the work of thousands of hands.

Architectural appreciation aside, it wasn't until Jaisalmer, in the Thar desert, the last stop on the Indian railway, and the closest city to the border with Pakistan, when I had reached a peak of frustration and irritation, that the current began to change.

Jaisalmer fort from the ramparts

Jaisalmer fort from the ramparts

We reached Jaisalmer on the evening of the third day out of Dehli, and I stayed my first night in Sona Hotel, a slovenly place with a distant view of the fortress which is the city's principal attraction. That night I was harassed (I'm sure he would say regaled) by the hotel owner, and both the company and the meal caused an illness that dawned mentally the next morning, and physically that evening. That morning, putting on my hat and sunglasses like a shield, I began to cry. When I left my room, I could barely even speak to my driver.

Jaisalmer fort dates back to 1156 A.D., and I am told that it is the only structure of its kind in the world that still has people living out their lives within it. As charmed as I was by the place, the only word that I could muster for the hawkers was, "no!" It's a remarkably effective word when conveyed in the right tone. I spent the morning wishing I could stay the night in one of the many hotels within the walls. Unfortunately, I was scheduled to take a camel ride into the desert that night. Around 11 am, an hour before my scheduled rendezvous with my driver, I stopped for refreshment in a hotel with a shaded, quiet, rooftop restaurant. life within the walls

life within the walls more signs of life

more signs of life

In that restaurant I met Damien, a poet from Dublin who has been working on an epic for 6 years; he plans to finish the work during his next 5 weeks in India. We talked for a while, and he helped me to see that I could indeed change my itinerary, and I did just that. After the requisite pain in my ass involved in changing a travel plan that I was told had "total flexibility," when I bought it, I met my driver, two hours late, and told him I'd be staying in the fort. Then, Damien and I rented motorbikes and drove to an abandoned village in the desert. village temple

village temple

As I sailed along the hot, open road, I thought about the scooter accident I had this Spring; I remember so clearly hearing a thunk, and then flying through the air, in one of those moments that seem as long as your whole life, thinking, "Wow, neato!" That was the thought I had before I hit the ground, and is the opposite of the rattled feeling that followed the impact and stayed with me for a week. Half the reason I was rattled (the other quarter being my aching bones and the last quarter being my damaged scooter and broken phone) was that I couldn't comprehend that inital thought. I was injured; why would I find that thrilling. Isn't that a dangerous, even stupid, attitude? I like life; why would I enjoy having it threatened? Then, unsuccessfully pickpocketed in Mongolia, I had the same reaction, and the same questions arose. empty temple

empty temple

Finally free of my ever-waiting driver, and in control of the wheel again, I realized that those moments were so lucid because they were completely unexpected. That car hit me from my left while I was looking right; that bandit stepped into a path that I thought was clear. As long as I can remember, I've been running mental laps about something or another. You might not know it to look at me, but I've always had at least the next minute of my life under control. When I was a teenager I drove myself nearly mad planning routes around our house. For some reason, maybe laziness, I was concerned with space; I always wanted to take the fewest possible steps to accomplish the list of tasks I had in my mind. God forbid I should have to go upstairs twice or forget my jacket in the kitchen and have to go back for it. After my father died, in my early twenties,the obsession, unnoticed by me then, became time. I spent years being so concerned that everything was a waste of time that I couldn't concentrate on anything at all, absurdly wasting a lot of time. strange god

strange god

Happily, I have finally broken the loop, but I still spend a lot of energy trying to exert control over whatever is around me. I take note of what's at the next corner and know which way I'll turn long before I arrive. When I enter a restaurant I choose a seat based on the possible consequences of the restaurant's layout and the situation of other patrons. When I wake up in the morning I make a mental plan of my day, and it costs me considerable energy deciding in which order to do errands. What I mean is, every day is full of expectations, assumptions, and preoccupations. This way of being takes the immediacy out of living; nothing can be just as it is.

Jain temple in the fort

Jain temple in the fortTaking refuge from the sun in the village's abandoned temple, I was reminded of an art history class, during my undergraduate days, when my teacher showed some slides of Pompeii; I'd always had vague dreams about travel, stemming from discontent, but that was the first time I saw something that I knew I had to see during my lifetime. One year later I left North America for the first time, and on a trip around Europe, I went to Pompeii. I was dissapointed. There were tourists everywhere, and all the people drained the place of the mystery it had in those empty photos. Still, I dutifully looked around, and after about 2 hours, it started to rain, at first in drops, then in torrents. Everyone left, except for me. I was wet through and through as I walked the sunken streets that had become canals, but the sudden rain returned to me that empty ruin in my imagination. Still, I couldn't quite hear the place, because I couldn't stop listening to the spinning of my own mind.

Likewise, the palace in Bikaner couldn't impress me because I brought too much me to it. Palaces are already a part of my fiction, something I have noted and filed away. And how many other things do I fail to fathom in a day, because I am not listening while I automatically overlay them with what I think I already know. When something hits you out of the dark night, whether it's a car or a birdsong, you, being taken completely unaware, have no choice but to know, if only for a moment, that there is a world outside of your mind. When someone, at high noon, steps into a path you thought you had already plotted, your body is suddenly seperated from your mind, thrown into a world you did not create, and you know, briefly, brightly, that you are existing in it, that you are alive.

Thank god I wasn't on that camel safari, because by the time I returned the rented scooter and entered the fort, I was having intense stomach cramps and cold sweats. I suffered through the night and left Jaisalmer the following afternoon, after one last stroll around the fort. I have come to terms with, and even appreciate some aspects of, the absurd luxury of having a car and driver. And I've met several travelers along the way who, having studied the Lonely Planet extensively before their arrival in India, are on the same kind of tour at the same kind of price, so I don't feel like such a sucker. I'm sure that there is plenty of inconvenient travel in store for me, so for now, I am content being whisked around this legendary land in my magic car(pet).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home